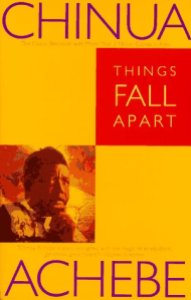

If I were making my desert island list of fiction, my top four would be, in no particular order, Bleak House, My Antonia, Middlemarch and Things Fall Apart. I initially read Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe to prepare for an assignment teaching Non-Western Literature in Translation to community college students. My love for this book never diminished, and I eventually also taught it in Introduction to Literature classes, where it worked in tandem with Greek and Shakespearean tragedy.

If I were making my desert island list of fiction, my top four would be, in no particular order, Bleak House, My Antonia, Middlemarch and Things Fall Apart. I initially read Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe to prepare for an assignment teaching Non-Western Literature in Translation to community college students. My love for this book never diminished, and I eventually also taught it in Introduction to Literature classes, where it worked in tandem with Greek and Shakespearean tragedy.

But I was interested in it as the most gripping illustration of what happens to religion in the face of modernity I’d ever read. There is a scene at the end of Part Two of the novel, where our hero Okonkwo sits before a fire and considers what it means that his son has followed the colonialists and become a Christian. In the tribal worldview, the elders perform ritual ceremonies and even tribunals in the form of a masquerade. They put on elaborate masks and become inhabited by the spirits of the great ones who have died. The people call forth this Masquerade. Another of my literary heroes, Wole Soyinka, writes in a memoir about his childhood that the masquerade figures, while completely recognizable as men from the village, were experienced as utterly supernatural (and terrifying) figures. It was simply a cultural reality that the Masquerade was the embodiment, the possession, of the great elders.

Okonkwo believes that he will someday join these spirits. And the book describes this moment: “Suppose when [Okonkwo] died all his male children decided to follow Nwoye’s [his son’s] steps and abandon their ancestors? Okonkwo felt a cold shudder run through him at the terrible prospect, like the prospect of annihilation. He saw himself and his fathers crowding around their ancestral shrine waiting in vain for worship and sacrifice and finding nothing but ashes of bygone days, and his children the while praying to the white man’s god. If such a thing were ever to happen, he, Okonkwo, would wipe them off the face of the earth.” But of course, this is just bluster– this is his primary characteristic, his brute power, become moot. He would be trapped in the earth, impotent as ash.

Okonkwo believes that he will someday join these spirits. And the book describes this moment: “Suppose when [Okonkwo] died all his male children decided to follow Nwoye’s [his son’s] steps and abandon their ancestors? Okonkwo felt a cold shudder run through him at the terrible prospect, like the prospect of annihilation. He saw himself and his fathers crowding around their ancestral shrine waiting in vain for worship and sacrifice and finding nothing but ashes of bygone days, and his children the while praying to the white man’s god. If such a thing were ever to happen, he, Okonkwo, would wipe them off the face of the earth.” But of course, this is just bluster– this is his primary characteristic, his brute power, become moot. He would be trapped in the earth, impotent as ash.

Okonkwo’s world is brutal and Nwoye, a sensitive child, is crushed by an early action by his father. Nwoye is no brute warrior, and he goes where he finds opportunity and the promise of a more gentle life, with the powerful white colonials. In the final part of the book, the colonial government brings down its own hammer, that of the Law, and the tribe’s culture is completely destroyed.

What has always moved me about this book is the portrayal of the collapse of a religious world view. It resonated with me at the time as a reflection of how a stifling experience of Christianity in my youth had made it very difficult for me to hold onto God. And it helped explain the violence and grief on all sides when I didn’t continue to practice in that very stifling form of Christianity. But I actually think it was part of a larger experience I couldn’t even see at the time: the struggle to live Christianity in an age where the Christian worldview, the lived experience of knowing Jesus Christ crucified and risen, is almost completely beyond our grasp. In a world where Reason of a rather shallow sort reigns over all, where skepticism and irony are the primary modes of discourse, there is little room for any kind of mythic or what I can only call a sacramental reality. What I want to cultivate, and what I feel is very hard to take hold of, is a Christianity with a rich and full mythical dimension.

That is why I am a Catholic– because it is in the context of the Liturgical Year and the Sacraments that the whole story makes sense. It is there that I hope to be informed by a Christian worldview and have a lived Christianity.

I think in this historical moment it is very difficult to think at all about a worldview. In this world where the highest value is “choice” and there is seemingly no agreement even on fundamental values (we all claim the same values but in practice define them so differently that we end up looking at each other in utter confusion), it is hard to know what is gained and lost from generation to generation. And I admit that when I meet older Catholics, as I do often these days, who are fully imbued with faith and lamenting that their children and grandchildren are no longer practicing Catholics, I don’t really understand the language they are speaking when they talk about their faith. I don’t really understand their experience. But, thanks in large part to Chinua Achebe, I do understand their loss.

The jig is up not just for the Africans whose tribal religions and worldviews were wiped out by Christian European Modernity, but for all of us– for the way Christian European Modernity and American Modernity, Western Modernity, what my husband talks about when he talks about Liberalism (which has nothing to do with liberals) has done to take out all belief systems. To flatten reality. To make a faith life difficult and isolated and uncertain and lonely even inside of churches and families.

Perhaps our only chance is writers like Chinua Achebe, who died yesterday, writers who can show us the depth of our changing world. Let us strive to be readers who will not take books like this and say “we are the Colonists” and “they are the natives.” Let us see this is the state of our world and this is all of us– what we have done and what world we all live in. What we have lost and what has fallen apart.

This is beautiful, Susan. You have given me insight into other cultures as they cling to their traditions and beliefs and the perspective of Paul when he said, But whatever gain I had, I counted as loss for the sake of Christ. Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the

surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For His sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christ…(would love to write it all because it is so amazing!).

And yet He preserves the stories of His faithful ones as He has put gifted writers like you into the lives of the aging saints who are still with us, to leave a legacy and account of that generation, together, you and they, “in the midst of a crooked and twisted generation,… you shine as lights in the world, holding fast to the word of life”

Pingback: We Sinners, a review | susan sink